2 March 2004 | Vol. 4, No. 1

A Quiet Life

In the dark early morning of a heavy snow there is the sound of metal against rock, a scraping, low at first but relentless, insinuating. It worms itself into my dream, insisting that I awake. Outside it is dark but I can make out the figure of a man with a shovel. He stands in the snow, gaunt in a white greatcoat, the chinstrap of a World War I campaign hat framing a face of slight proportions. Is it a boy playing tricks, or the lone soldier of a ghost battalion? The form seems elderly but its motions are strong and determined as it lifts great shovels full of snow and tosses them behind. From a gray haze of sleep comes the slow realization that an old man has been shoveling snow from my driveway while I slept. I look more carefully into the dark. It is Ojisan, the retired farmer who lives across the street. Have I slept too late? It's only five a.m., still hours from first light, not an unreasonable time to be in bed, even in rural Japan. Will there be gossip about the lazy foreigner who sleeps late? I will him to go away before the neighbors look out at their own snow covered sidewalks. Ojisan keeps on shoveling, working his way closer to the house. I open the front door. It scrapes up a mound of wet snow. Ojisan is bent over, leaning his weight into the shovel. He looks up, startled. I invite him in, but he refuses, shyly backing away, bowing, bowing, until he is across the road and obscured by falling snow. Later that afternoon there is a knock at the door. It is Ojisan with an offering of saké and potato cakes.

"I'm disturbing you," he says, more a greeting than an apology. He takes off his boots and places them neatly facing outward in the entryway. For the first time I see his face close up. His eyes are deep-set, contemplative, inward looking. The thin line of his nose, his sharp, angled cheekbones are bird-like. His face is dwarfed under the wide brim of his campaign hat, revealing the hairline of a young man. With a callused hand he combs back a gray crew cut. He fills my saké cup and I take the bottle, as it is done in Japan, and fill his. We toast, "Campai." Ojisan sits silently drumming his long fingers on the table. They are farmer's fingers, roughened from decades of tending sugar beets and potatoes. He laughs a low, self-satisfied laugh and looks around the room, immensely pleased with himself. He has crossed over. He is in the house of the foreigner.

Looking down on the village from Kanayama mountain, past the eighty-one steps that climb to a small Buddhist temple nestled in a grove of larch, two houses, one large, one small, can be seen opposite each other on the street below. The larger one is a modern, multi-room dwelling with a new metal roof, aluminum siding, and a freshly blacktopped driveway. Built into a small hill, it sits slightly above its neighbors, making it seem separate and aloof. It looks like a place where rich people might live. But this house was never intended for the rich. It is the house provided by the town for their invited foreigners, their gaikokujin. It is where I am living with my wife and young daughter while making a documentary film about life in this rural village. The small frame structure across the street is old, weather beaten and bleached white from decades of sun and rain. It's a one-room house with ornate sliding doors made of glass and paper screens long ago turned brown with age. A patch of tarpaper torn up by the wind hangs from the roof in shreds. There is a certain neatness to the disrepair. Someone has attended to a collapsing doorjamb, replaced rotting sideboards and re-papered a section of roof. But eventually, even the most meticulous repairs, like cosmetics and creams, cannot hide age. The old house has a deep, settled look, as if its roots were planted before the town arrived, before there were farms and people in these mountains, long before foreigners thought of coming.

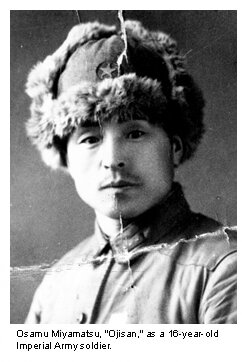

The man who lives in the house could be as old as the place itself. His name is Osamu Miyamatsu, a retired farmer who lives alone. Everyone calls him "Ojisan," which means Uncle, and is what all old men in Japan are called. It's an honorary title, a trophy of warm and public familiarity awarded for living to be old. For an entire month before we spoke, I watched him on his early morning walks, his gait oddly soldier-like, his old legs cutting a trail through deep snow or trudging up the eighty-one steps to the log shrine where a statue of Buddha sits serenely in the cold. If he isn't walking by first light, he is hoisting his 85-year-old bones up onto the roof of his small house. Balancing on the roof he shovels a few inches of accumulated snow, one end of a rope tied around his waist, the other around the stovepipe . From the peak of this lookout he waits for passersby, and in a small ritual of familiarity, neighbors, old themselves, exaggerate their alarm and admonish him to be careful. Ojisan waves them off, laughs, checks his balance and continues to push snow over the eaves.

Ojisan sits at the table, unsure of what to do. He considers the map of the world on our kitchen wall. On this map, borrowed from the local elementary school, the Japanese archipelago is in the exact center. America is an orange mass near the right edge, which bisects the Atlantic Ocean. It is a disorienting view of the world for a North American. Ojisan carefully studies the outline of America, as if pieces to the puzzle of these foreigners could be found there.

"It's a miracle I'm still around," Ojisan says in his sing-song rural accent. "Considering everything that's happened—the war and the bombings, the floods from the Sorachi River that took our house and crops. My wife had a premonition that I wouldn't come back from the war," Ojisan says. "In a dream she saw me floating dead in the sea. She thought she would never see me again, so she sold our fields and sold our horse. What good is a farm and a horse to a woman alone with little children? But I did come back. I came back and there was nothing. The land was gone, sold. My wife had a few thousand yen, but it was worthless because there was nothing to buy. We couldn't even buy a pair of socks or a towel. What good is money when you don't have land? I cleared a garden patch deep in the mountains where I could plant pumpkins and potatoes. The only reason we didn't starve is because I'm a farmer and can make things grow. I don't talk to my children about the past, because when I do their eyes glaze over. They look at each other and say, 'There goes Father again.'"

The next day at the Farmer's Co-op store, Sato wraps up my fish and says, "So, you had a visitor last night." Nakaseko, the school principal, telephones to express his appreciation for my kind treatment of Ojisan. While I am out walking, longhaired Otani, the town headman, stops to chat and smiles approvingly. "I understand that you like Japanese saké," he says, his white hair fluttering in the wind coming down from Kanayama mountain.

When I first see Kanayama village, densely clustered along the green Sorachi River valley, I am drawn to its serene, pastoral beauty. The reception I receive there is markedly different than in other Japanese towns. I sense no fear or apprehension. I meet with the Rojin Kai, the Elders' Association, whose members, many well into their nineties, line up to shake my hand. I meet with the PTA, its young members are shy but soon get up the courage to try out some English phrases. Intuition tells me that this is the right place.

I propose to the Kanayama Council that I come to their town with my family and equipment, to live and work for one year. I explain that I want to make a documentary film about the community, starting at the school and following the concentric circles that wind from there into the lives of the village families. I explain that I am looking for a partnership rather than "permission." They are astonished. They are alarmed. No foreigners have ever lived here before. What would we eat? How would we live? I assure them that we need no special care, that we can eat what everyone else eats and can live the same way every family in the village lives. Discussions are held, the school principal and the mayor consulted, the Elders Association and the PTA called in for opinions. After the logistical considerations are dealt with, the film project itself is discussed. The idea of being the subject of a film, of having the town, their own town, framed in the distinctive light of a movie screen, becomes intriguing and then flattering.

The town fathers have our best interests at heart. Once their decision is made, their commitment to the project seems unshakable. The old village clinic, abandoned years before when a real hospital was built twenty miles away, is refurbished at considerable expense and given the benevolent name of "International Friendship House." This will be our home for the next year. It is an ideal location, one block from the school and in the middle of everything. Our house will be rent-free. The town will pay for utilities and provide us with a car.

Out of genuine kindness and a particular Japanese solicitude, they want us to be comfortable in the way that foreigners like to be comfortable. Only no one really knows what that way is. It has to be imagined. A combination of materials are assembled for the house: new wood floors and new tatami mats smelling of fresh cut grass; a sit-down flush toilet installed and fitted with a heated seat and musical toilet paper roller that plays "Sakura, Sakura" every time the paper is pulled. An odd assortment of furniture is rented for the year—a long kitchen table, several folding chairs, a black vinyl sofa, a metal desk and two large console televisions. The house takes on a strange ambience, an amalgamation of elegant Japanese simplicity and utilitarian motel room decor.

Every few days, Ojisan returns, always carrying a bottle of saké and a plate of food. In what has become a ritual, he walks into the kitchen, places his hat on the table, pours saké and begins to talk. Soon, though, the ritual changes. He starts coming every day, earlier and earlier, until finally the doorbell rings while I am still in bed. Julie, who has been up since six with our daughter, opens the sliding door to our tatami room and shakes me awake.

"Time for your saké party," she says. "Ojisan is here." It's seven a.m.

He starts bringing friends, elderly farmers and their wives whom he proudly leads across the frontier, into the house, directly to the kitchen where he supervises the laying out of food and the seating arrangements. The visitors politely sip saké and look around, dutifully impressed with Ojisan's new role as international ambassador, their heads bobbing in abbreviated bows whenever our eyes meet, unable to hide their amazement at being in the house of a foreigner.

Above Kanayama, moist, heavy air blown north from the warm Pacific collides with a steady, uncompromising Arctic flow moving south from Siberia. The violent mixing produces turbulence and snow, three feet by December, nine by March. First, a white powdering over the sugar-beet and potato fields, then a steady fall, day after day until Kanayama is a place of monochrome views, its streets a twisting network of white tunnels. On sunny days the town is a cacophony of shovel blades scraping at snow, pushing and pulling it in every direction. When the sidewalks are clear the streets become alive with activity. People are strolling, praising each other's work, gossiping with neighbors who lean over their shovels to talk, as if they were backyard fences.

Ojisan is at the front door, smiling his amused smile, holding out his bottle as if offering a passport for inspection. He takes his usual place at the kitchen table and we drink. It is barely eight o'clock. He has been up since four and has already shoveled his roof, sidewalk and road, and now he is ready to relax into talk. I think of the deep, cut-grass smell of the tatami mats in the bedroom and the sleep I can salvage when Ojisan finally leaves. But he has no intention of leaving. He takes off his coat and his vest. He feels good. The saké loosens his memories and floats them to the surface where they are detailed and given voice. I bring out my tape recorder and switch it on. Since his visits started I have recorded everything and now have more than ten hours of stories and conversation. Ojisan likes the tape recorder and the formality it brings to the room. He watches the red light flicker on, and like a virtuoso readies himself to perform, a finger punctuating the air like an exclamation mark.

"My daughter lives in Tokyo," Ojisan says. "She said to me, 'Father, this city can break your heart.' It's true! People don't talk with each other calmly there, like we do. If my curtains are not pulled back by nine o'clock in the morning, someone comes to check, but in Tokyo, you could die in your apartment and no one would ever know it. I went to visit my daughter but I left after a few weeks. She begged me to stay, but I just couldn't. In all that time not a single person said, 'Good morning,' or anything like that. They just ignored me and passed by. It's so annoying, but there is no use getting angry at them. They're not going to change."

The next morning Ojisan is back before 7:00 a.m. It's snowing heavily outside and he is in an ebullient mood. I drink my first cup of saké as the eastern sky begins to lighten. I can't keep this up much longer.

Later I visit Nakaseko, the school principal, to ask his advice. I explain the problem and he laughs. He understands implicitly that Ojisan's daily offerings of saké are part of a delicately balanced reciprocity.

"You are caught in the trap of kindness," he says, smiling. His wife brings tea from the kitchen and a plate of the bean cakes she knows I like. I realize that in spite of all the hours I've spent at this woman's table, I don't know her first name. I call her "Okusan," which means, wife. This is what I'm expected to call her, since she is the wife of my friend. The convention of appropriateness dictates that I view her from the position of the person who introduces us. Nakaseko explains my situation to his wife, and she laughs until tears come to her eyes.

"The old men have stamina for drinking," she says, unable to suppress her laughter. "Go walking with him, up to the mountain. He knows everything about plants. Change the routine." Nakaseko says, "As a general rule, when drinking saké, take only small sips."

Crisp, clear weather follows weeks of constant snow. Ojisan is able to resume his regimen of early morning walks and for the time being, this solves the saké problem. I start to walk with him. He leaves a little later to accommodate me. I watch his thin legs move steadily up the trail on Kanayama Mountain, legs that have stood in fields and pushed loads through these hills every day since he was nine, legs almost a half-century older than the pampered ones that follow him. Ojisan shows me how to find sansai, the mountain vegetables he harvests to make tempura. We pick a basket full of young ferns that he will turn into pickles. He points out the plants he uses for home remedies.

"This one is excellent for a cold," Ojisan explains, pointing to a low vine half buried in the snow. "I don't use it because I haven't had a cold in over thirty years." From the top of the trail we can see our two houses down in the village below. Together they look like a mix-up in time, a strange juxtaposition of histories.

Months have passed and I still have not been inside Ojisan's house. He has never offered an invitation and I have never asked. I prepare a gift of fancy senbe crackers, bought from Sato's store, and wrap it carefully. At Ojisan's door I yell out the greeting that is half apology. He opens the door and looks at me, surprised. He takes the extended gift, says a formal thank you, turns into his dark room and slides the glass door closed behind him. I am embarrassed. I stand there wondering what I've done. Perhaps I should have warned him that I was coming, so that he could prepare. A first visit requires formality, a sense of order, and good food to serve.

That day and the next, Ojisan does not venture across the street for his accustomed visit. Now I'm more concerned. I visit Nakaseko to ask his advice but at the last minute decide to keep quiet. Instead we talk about the upcoming sixth grade graduation.

My relationship with Ojisan is defined by patterns of appropriateness. We are not equals. This is a society where one ascends to privilege through age. I am half his years and so it is appropriate and expected that he be an honored guest in my house. Ojisan, who at 84 years old invests little energy worrying about what other people think, trades on the privileges of age to the fullest. When he crosses the threshold of my house he is, in a very real sense, entering a proxy foreign land. I listen to his stories (perhaps I am the only one in the village who hasn't heard them before) and with enthusiastic nods and blinking tape recorder, give them a new power. This had been the pattern of our relationship. It was set and determined. We acted out our appropriate roles in the confines of this setting. Any Japanese would have known to leave it alone.

The next morning I decide to try again. I am after all an American, who is put at ease by informality. I walk the few steps to Ojisan's house with a plate of fried oysters and a package of Chinese tea. He sees me coming and waits at the open door, motioning me in. He is more subdued than the Ojisan who visits across the street.

In the one room of his house, Ojisan and I sit at a small table cluttered with books and magazines with titles like Medicinal Plants of Hokkaido and Remedies from the Forest. A space has been cleared between us just large enough to accommodate a china teapot, two cups and my tape recorder. A gas heater in the center of the room radiates an overbearing heat, boiling away the tea that remains in the black kettle. Two small orange trees in large pots dominate a corner of the house. It is winter but they are in full bloom. Snapshots of the trees in various stages of growth hang on the wall like family portraits. There is a framed picture of the late Showa Emperor, Hirohito, and beneath it, photos of Ojisan's grandchildren posing with Mickey-san at Tokyo Disneyland. From his window I can see the gate to the village shrine, and my own house directly across the street. On the road, noisy kindergarten children walk by in single file, following a teacher holding a flag. Their yellow helmets reflect the afternoon sun like a row of bobbing sunflowers.

Ojisan opens the gift-wrapped box of white senbe crackers from my first attempted visit, and then reaches for the kettle to fill our cups with strong green tea. Its pungent smell mixes with the scent of orange blossoms. One of the two orange trees has its branches neatly tied with blue plastic bandages. Ojisan examines the blossoms closely.

"I put this one in the garden for the summer and mice chewed off the bark," he says, pulling back a bandage and inspecting a graft where tender new bark is growing.

"The wrappings have to be changed every day and a salve put on the grafts. My daughter wants me to come to Tokyo for the New Year holiday, but who would take care of the trees?" I suppress a sudden impulse to volunteer for the job. What if they died under my care?

"Couldn't your son do it?" I ask. Ojisan's eldest son, a retired logger, lives on the next street.

"He's more skilled at cutting trees than healing them." On the plywood counter next to the sink sits a small rice cooker, two plates, two bowls and an assortment of mismatched chopsticks—an efficient assemblage of tools for a man accustomed to living alone.

"Why don't you live with your son?" I ask, and immediately regret the directness of the question. In Japan it's rare to find old people living alone. Oldest sons have the responsibility of providing for aging parents, an obligation usually accepted without question.

Ojisan digs a photograph out of a drawer and hands it to me. The picture is of an unattractive middle-aged woman with narrow eyes and a mean mouth. "My daughter-in-law," he says, in partial answer to my question of why he doesn't live with his son.

"I've learned a lot by being alone. I nursed my wife, I cared for her for eight years," Ojisan says while lifting boxes and opening drawers until he finds a shoebox filled with photographs. He holds out a photograph of an elderly woman in a kimono standing stoop-shouldered in front of the Meiji Shrine. She is so small in the frame that her face is almost indistinguishable from the pattern of her kimono.

"It was in the eighth year of her illness when she finally died. I didn't realize how exhausted I was. The biggest problem was making meals. Rice alone is fine for me, but I couldn't feed her the same thing three times a day. She looked very tired and started dozing off. My daughter-in-law came in and waved a hand in front of her face and said to me, 'Father, she's dead.' I didn't want to show my tears. I looked after my wife for eight long years and the day before she died, she thanked me. She cried and kept saying, 'I'm sorry, I'm sorry.' I reproached her. 'What are you saying—we are husband and wife.'" Ojisan blinks back a tear. "All I ever really wanted was a quiet life."

Later that night I go to the school gym for a community volleyball game and there I meet Ojisan's daughter-in-law. She is a small round woman in her late fifties, with a generous smile and friendly eyes, completely unlike the sour face of the photograph. She thanks me profusely for "taking care" of her father-in-law, and then apologizes for the trouble he must be causing me.

"I hope he's not bothering you with his stories," she says. "He doesn't always remember when he's told them before." She insists that I be on her volleyball team. Throughout the game she cheers me on, shouting showy praise at my awkward serves. I am tempted to joke with her about Ojisan, to try and win her further, but decide against it as it could have unexpected consequences.

The next day I am back at Ojisan's house. He makes udon noodles and we sit talking easily while sumo wrestlers battle on TV. He brings tea and then a large envelope from his cluttered desk. Inside is a cassette that he puts in the tape player.

"The title of this song is, 'The Mother Standing on the Wharf,'" he explains. "It's about a mother waiting for her son who has gone to sea and will never return." He pushes the play button and I hear a wavering voice climb and descend a distinctively Asian melody. It is a solo performance in the highly emotional Enka style, made on his own tape recorder. When the song is over, he bows.

"The next one is about a family that goes to visit the temple where their son is a priest." Ojisan shuts off the tape player. "I'll sing this one for you myself." He closes his eyes and lets the song well up in him. He sings without hesitation, without self-consciousness.

I am old and dependent on my walking stick,

but son, I came here to see you.

The sacred arch of the temple's entrance penetrates the sky.

Oh, such a splendid shrine.

It's such an honor to be here.

Mother was so moved she cried.

We felt such happiness.

I am very sorry for this outpouring of feeling.

It's just like the lowly kite that gives birth to a falcon.

It's such a treasure to have a son like you.

Like a soldier who wants to show his medals,

I came here to see you.

Here, in Kudanza-ka.

Ojisan stops singing. With eyes still closed, he bows low.

"The next one is a love song," he says. "It's about a man who asks for his girlfriend, his childhood sweetheart, to come back to their village. She has gone to Tokyo and he knows that she is never coming back. His mother reminisces about their innocent childhood and wishes she would come back to Oiwake Mountain. When the girl left, she made a promise that she would come back, so he calls for his love in the song. From the top of Oiwake Mountain he cries out, 'kite-yo, kite-yo, come back, come back.' But of course, she cannot hear his cries." Ojisan begins. He cups his hands over his mouth when he sings out, "kite-yo, kite-yo," as if shouting from the top of Oiwake Mountain.

"Beautiful, but sad," I say.

"Sad, but sweet," he counters. "Young people say the songs are depressing, but they don't understand about sacrifice. They have only known luxury in their lives, so we can't expect them to understand the feelings these songs bring up."

Ojisan puts away his tape player and the cassette. He rummages through his desk and finds another envelope, a smaller one. Inside is a photograph. It is a portrait of a boy in the uniform of the Imperial Navy, the young face eager and open, the eyes unmistakably Ojisan's.

Ojisan puts away his tape player and the cassette. He rummages through his desk and finds another envelope, a smaller one. Inside is a photograph. It is a portrait of a boy in the uniform of the Imperial Navy, the young face eager and open, the eyes unmistakably Ojisan's.

"Sixteen years old," he says in a voice suddenly worn.

"You haven't changed much," I tease, but he is not in the mood for joking.

"As kids we worked and worked and were yelled at for not working more. That's all we did. Our parents didn't take care of us. They spent all their time in the fields. There was no choice for them but to work like that, otherwise there would have been nothing to eat. My parents needed me to work and watch the other kids so I had to quit school after the fifth grade. I was patient until I was sixteen and then I joined the army. Here, it's for you," Ojisan says, pressing the photograph into my hand. "A picture of a soldier with potatoes in his head."

In my own kitchen later that night, I put the cassette from my first interview with Ojisan in the recorder and hear his voice saying, "I am relaxed! Don't worry about me. You're the one that needs to relax." I advance the tape and Ojisan's voice grows more intense. The chair he always sits in is empty, the corner of the table where he puts his hat now piled with newspapers.

"I was drafted in the eighteenth year of the Showa Emperor, right at the start of the war. I had already served in the army for six years, but they drafted me again. I was assigned to a troop ship as a Marine guard. It wasn't very difficult work. The ship transported soldiers from Tsushima to Nemuro where they were sent to the fighting. We were just starting out for Nemuro when word came that all farmers were to return home. There was a food shortage so we had to go. We had to make this contribution to our country. Two hours after I left the ship, it was hit by a torpedo from an American submarine. Two thousand men were killed. They jumped screaming into the ocean. It happened on a beautiful day, under a blue sky, just like today's."

Snow is falling, lit brilliant orange by a line of street lamps guarding the gate to the shrine. Ojisan will be up at 4:30 to shovel snow. With pins I fix the photograph of the young soldier next to two neatly framed portraits of orange trees in bloom.

About the author:

Leonard Kamerling is a documentary filmmaker and writer. He teaches at the University in Fairbanks and curates the film collection at the University of Alaska Museum. Len can be contacted at

For further reading:

Browse the contents of 42opus Vol. 4, No. 1, where "A Quiet Life" ran on March 2, 2004. List other work with these same labels: nonfiction, memoir, editors' select.