2 December 2004 | Vol. 4, No. 4

Caravaggio's Rothko

Originally published as the forward to the Masters Revealed catalogue, The Whitney Museum of American Art, New York.

You've always feared that modern art was a sham, that a bunch of apes with Crayolas could do the same, if not better. I can prove otherwise in spades. An unknown game was being played, and when I uncovered its rules, the spontaneity of de Kooning, Kline and Pollock started to formalize under Coubert, da Vinci, and a chiaroscuro table corner of Manet's, respectively. But I didn't, as Newsweek and most of the others have portrayed me, set out to do any of this. It was an accident, I swear.

It all started in Rome. Caravaggio's Judith & Holofernes (1599) was acquired, ruthlessly, by the Galleria Nazionale d'Arte Antica in 2001 from an American 'private collector' unwilling to exchange public office for a scandalous proprietary investigation. Immediately upon its arrival, restoration work began which was to last late into the autumn of '03.

The tyranny of the upper-reaches of the museum had reduced staff to the point where each painting was the responsibility of a single craftsperson, but because of the international attention of the acquisition, I was hired as junior assistant to hasten progress on Judith. As junior assistant, I was given most of the pots and pans, as we call it in the trade, to do, which in this case meant the drapery, background, and clothing surrounding Judith, who stands, in the center of the painting, over her lover still in bed, hacking through his neck with one hand while holding his head steadily by his hair with the other, watched over by an old crone on her left, looking like her horse is about to come in. However, because of the over-zealous board of trustees in Rome, the unveiling of the work was further pushed forward, and I was also asked to complete the neck and chest of Judith, since the odd foreshortening of Holofernes' right arm was giving my superior more than her share of trouble.

It was there, in the shadows cast by Judith's neck upon her breast, that I was to make the discovery that slit modern art in two. Hidden in the creases of her neck, which I was working on with a mild emulsion cleaner, using nothing more than an admittedly quirky magnitude-10 monocle, I discovered Mark Rothko's Number 9, 1950, (the first of his large, abstract color series that was to make his name in that first generation of New York Abstract Expressionists), nestling in the darkness. The 400-year-old painting contained an exact, miniature replica of Rothko's monumental canvas, a postage-stamp version of the American original, hiding in the brushstrokes of Judith's neck's shadow dissolving into her breast, deepened by a dark crease in her flesh. Like a human face trapped in the pattern of a moth's wing, Rothko's painting was just sitting there, waiting for me to work out the hows and whys.

Which is exactly what I did. At first, I only assumed that Rothko's powerful ether could be found in any mussed-up paint palette, if you looked hard enough. But it couldn't. And then the whole museum got involved, and it just flew out of my hands.

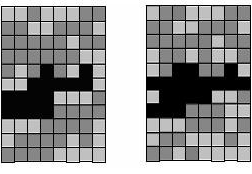

The best way I can show you is to take the Caravaggio section (ca. 3 cm x 4.5 cm) and rotate it to the right 37 degrees so it's standing upright. Then scale the Rothko picture (ca. 150 cm x 225 cm) down to 1:50 and reduce the color to just three grey tones. Covering the surfaces with an 8 x 11 grid, you can easily see the similarities that struck my monocle, as illustrated in the following figure:

On the left, Caravaggio's Judith, and on the right, Rothko's Number 9. Notice the similarities in the upper-right quadrant of the picture, the bold left-to-right stroke in the center, and the strong vertical slant in the lower half. There is a 74% match. (Thanks to Pete Elfstrom for the illustration.)

There has been both wild speculation and renewed research into connecting names and dates, and places and collections. In my case, Rothko and his wife Mell were in Portland in October, 1948, for Rothko's mother's funeral, 50 miles from the private collection Judith was pried out of, as I mentioned, a few years ago. Did he take Mell on a country drive, to ease tensions over a family that already famously didn't get along, taking her to a known collector's house, looking for a new buyer or maybe meeting up with an old acquaintance, even an old family friend, since Mr. Rothkowitz had been the collector's pharmacist for at least 13 years prior? In the mid 40's Rothko was as famous a self-promoter as he was as a recluse in the 50's.

But how was Rothko to get so close, to peer into the work? He must have had an agenda to follow, for although his was the first fraud found, it was not the first made. It is believed that Robert Motherwell's Western Figure is the earliest known fake, although this is assumed solely on the basis of its formerly cryptic reverso inscription, "You shall never learn whence I came," since its presumed predecessor has not yet been found.

That could have been the start, Motherwell passing on his joke during a late night at the Cedar Bar, the others slowing gathering around, putting the joke on.

And that's what you'll be seeing here today; copies and originals, side by side, with detailed illustrations diagramming, to the best of our knowledge, how, where and when they were made, hopefully leading to a new era of appreciation. The implications of these discoveries are as yet unknown, but Abstract Expressionism as a spontaneous application of paint in creating a nonrepresentational composition is a definition that The Whitney's Masters Revealed series hopes to revise significantly.

About the author:

Brian Willems is an American lecturing in British and Irish literature at the University of Split, Croatia. His work has recently appeared in Pindeldyboz, Yankee Pot Roast, Über, Poor Mojo's Almanac(k), The Palaver Omnibus, The Edward Society and Retort Magazine. You can reach him at .

For further reading:

Browse the contents of 42opus Vol. 4, No. 4, where "Caravaggio's Rothko" ran on December 2, 2004. List other work with these same labels: fiction, flash fiction, experimental, metafiction.